HomeFeaturesWarhammer 40,000: Space Marine 2

Why play a fascist? Unpacking the hideousness of the Space MarineHammer time

Hammer time

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Focus Entertainment

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Focus Entertainment

In order to makeWarhammer 40,000: Space Marine 2enjoyable, Saber Interactive had to make the Space Marines less like Space Marines. That’s to say, less like “semi-lobotomized, hypnotically indoctrinated slave-soldiers in thrall to an uncaring (and possibly non-existent) god”, inthe words of Rick Priestley, primary writer for the originalWarhammer 40,000: Rogue Traderrulebooks back in the 1980s.

In Warhammer 40,000’s supposedly satirical, definitively grimdark Imperium Of Man, the Space Marines are the genetically engineered sons and warrior-monks of the Emperor, a messianic figure reduced to a dreaming corpse on the Golden Throne, whose immense psychic emissions serve as a kind of spirit lighthouse for interstellar travel. The Space Marines are grotesque supermen clad in motorised armour, who exist to exterminate the alien, the mutant and the unclean. They are the ultimate embodiment of patriarchal xenophobic fascism. This is a source of some irony, given that they themselves barely qualify any longer as human, according to the ideals of uncorrupted humanity they champion.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Focus Entertainment

Hollis-Leick and narrative director Craig Sherman pushed back on some of the “do’s and don’ts” they received from Games Workshop about Space Marine vocabulary. They deviated from the suggested phraseology to make Titus and his comrades sound less “strange and antiquated”, less like the Spanish Inquisition, and more like soldiers from real-world present-day militaries. “Space Marines don’t necessarily say things like ‘dismissed’,” Hollis-Leick observed. “There’s a line in the game where Acheran says ‘company dismissed’ and they really wanted me to change that to ‘brothers, attend your duties’, or something. But it’s three words instead of one, and if that model was applied to all of the language in the game, I really strongly felt that people wouldn’t get it.”

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Focus Entertainment

It’s saying something about how accustomed I am to the ostensibly parodic figure of the Space Marine being portrayed as a hero that I didn’t really question this desire to make you “like” and “get” the “fanatical killing machines” at the time. To be clear, I don’t think Saber are deliberately and consciously trying to kindle empathy for literal fascist enforcers in Space Marine 2. Much of the above reasoning is grounded in ostensibly neutral, best-practicey questions of craft and characterisation.

Still, it would have been useful to dig into what it means to make Space Marines likeable, because Warhammer 40,000 today has an issue with certain groups of players actively identifying with them. Exactly how far this extends is unclear, but the game’s fascist subculture is significant enough that Games Workshop have felt moved to publish statements disavowing outright bigots, and ‘reminding’ the tabletop community that the Imperium Of Man is a send-up of fascism, of empire and of murderous patriarchs, not an endorsement.

The company’s outspokenness is praiseworthy, and there’s the argument that much of this is out of their hands: every community harbours extremists who read against the grain. But Games Workshop are also guilty of hypocrisy, here, in that modern-day Warhammer 40,000 is a far cry from the “satire” it once claimed to be. Back in the 1980s, Warhammer 40,000 could have been called counterculture, its loopyur-fascistuniverse a warping of Thatcherite Britain and the Cold War, its artworks and characterisations subversive in their feckless jamming-together of devices from 2000 AD comics, Milton and Dune. But over time, the license holders have softened and consolidated the wackier elements in order to make Warhammer 40,000 more sellable - a gradual mainstreaming that has transformed the Space Marine in particular from a crazed and distorted thug into a stoical, comradely and devout ‘necessary evil’ pitched against a galaxy of apocalyptic terrors.

Image credit:Games Workshop

In 2023, the writer and designer Tim Colwill publisheda comprehensive accountof how Warhammer 40,000’s reverential militarism and apocalyptic fascist sentiments have slowly overgrown the more whimsical and pluralistic aspects of this “sci-fantasy” setting. He discusses how the Space Marine, Games Workshop’s best-selling miniature, has ‘matured’ from a jackbooted bully into the doughty and dogmatic paladins we see in Space Marine 2, endowed with a “tacticool” aesthetic ready-made for modern third-person shooters, which “cleaves away from the colourful exaggeration of the 1980’s and much closer to the real-world military gear of special forces operators”.

It can be pleasing to inhabit a fiction where all the pieces are smoothly bolted together, working in lockstep. But teaching people to favour the consistency of imaginary worlds may also teach them to vilify disagreement and the entire practice of interpretation. At its nastiest, this mentality both facilitates and camouflages bigotry. Take the backlash against the concept of female Space Marines. That Space Marine recruits are all cisgender men is a commercial accident, albeit one that speaks to the boy’s club undertow of the wargaming scene: according to Colwil, Games Workshop simply couldn’t sell enough boxes of mixed-gender Space Marines, and rewrote the lore to justify only shipping male miniatures. Nowadays, this business technicality has become an article of faith among certain male players, which makes the introduction of a new, Marine-adjacent faction of mixed-gender Custodes not just an attempt to attract women to the game, but a form of heresy.

All this notwithstanding, I’m not sure the mainstreaming of Warhammer 40,000’s satire entirely explains why the setting has become so attractive to fascists that the license holders have felt moved to remind us that Warhammer 40,000 is supposed to be satire. The more complicated problem with Warhammer 40,000 is that the depictions of fascism it supposedly lampoons - the uniforms, posters, films and other artworks that drew millions in the 1930s and 1940s - are more compelling today than many anti-fascists would care to admit. It’s dangerous, Sontag says, to reduce fascism to “brutishness and terror”. Fascism survives because it offers things to aspire to - in Sontag’s summary, “the ideal of life as art, the cult of beauty, the fetishism of courage, the dissolution of alienation in ecstatic feelings of community”. These are relatively innocuous values and emotions that may also appear in, say, rock music, in superhero stories, at wargaming tournaments and sports events, and in earnest game developer paeans to “absolute brotherhood and sacrifice”.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Focus Entertainment

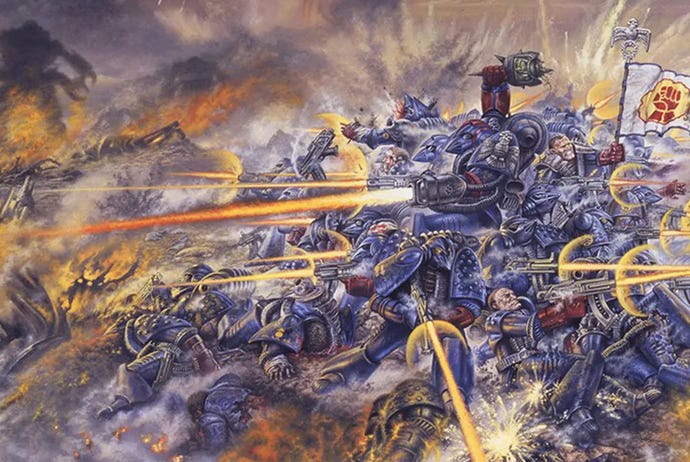

Speaking as an occasional enjoyer of Warhammer 40,000 (I loved Complex’s XCOMalikeWarhammer 40,000: Chaos Gate - Daemonhunters) I do think the setting actively channels various proto-fascist longings. Sontag’s characterisation of the hypnotic “fascist dramaturgy” on display in Nazi artworks and photography of Nazi rallies reads like a dissection of a Space Marine codex cover - the classic spectacle of the Marines piled up like crabs in a bucket, balanced between “egomania and servitude”, domination of others and submission to an almighty leader, “extravagant effort, and the endurance of pain”.

Almost a century since European fascism arose, we may intellectually understand such art for a display of hatred, and yet still feel drawn to it, perhaps because we live in grimdark times indeed. I think the “brutishness and terror” of Warhammer 40,000, the obviousness of its debts to the theatrics of tyrants like Hitler and Mussolini, may actually be what lends it “positive” appeal, in that embracing a monstrous taboo produces a sense of freedom from the hypocrisy that ‘all is well’. The Imperium is one of many cathartic dark fantasy statements about the hideousness of contemporary reality: it channels a conviction that our world, this neoliberal and imperial capitalist dog’s dinner, is not in fact the height of progress, but fundamentally awful and only getting worse.

At its most potent, the Imperium Of Man can be a fiction that renders all this disgustingly concrete and provides some relief, opening an interval for laughter and discussion. This, for me, is the point of its satire. But satire doesn’t really work when you commodify it successfully: the all-important historical context is lost as the business evolves over decades and moves between markets, and the need to sell a product encourages a more straightforward, positive identification with the radiant fascist tropes Sontag describes.

Image credit:Games Workshop

Dawn of War III – Announcement TrailerWatch on YouTube

Dawn of War III – Announcement Trailer

In the first editions of Warhammer 40,000, the Marinesappear more ridiculous than formidable. They are squalid gargoyles of flesh and circuitry. They are strung-out fashy gang-bangers in leather belts and onion armour. They are incompetent coppers,sneering schutzstaffel. They are silly and dysfunctional, leering between the number tables of the first edition like fairytale ogres playing at knights. Where today’s Space Marines appear evenly proportioned and graceful for all their bulk, much of the early art occupies a hinterland between linear depth of perspective and the flattened crowds of a medieval altar piece. The Space Marines of this era look false and ungainly,at once bulbous and glistening and smeared across the canvas. They are laughable. They are enjoyable grotesques.

Image credit:John Sibbick / Games Workshop

The setting has obvious topicality, but the fiction is too incoherent to be sustained political commentary. It reaches tentacles in all directions. It is a libidinal kit-bashing of everything the authors find intriguing or intriguingly revolting about their time. And at the core of all that ravenous world-building there is the Space Marine.

One of my favourite artworks from this primordial period is David Gallagher’sLost Patrol, printed onthe cover of White Dwarf magazine in 1992. It depicts a crowd of Space Marines and other Imperial goons descending a stair in some phantom dimension, with the suggestion of city architecture in the top corner. A couple of the Marines resemble the ones you see in Space Marine 2, with uniform armour and heraldry and a particular squareness of jaw, a glintiness of eye that has become canonical. But most of them look like press-ganged junkies in face paint and pretentious mohawks, leering at the shadows. Their costumes and equipment are unconvincing, snatched from a backstage wardrobe in passing. There are chainswords and Lawmaker-style modular pistols, but there are also gaudy penants and ribboned Tudor sleeves. The guy in bottom right looks like he’s bumbled in from a syncretic pagan re-enactment, with a laurel wreath and a feather dangling from his battleaxe.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Focus Entertainment

Still, revisiting artworks like “Lost Patrol” feels like a good start for anybody genuinely committed to the notional anti-fascism of the Space Marine, inasmuch as it dissolves today’s consecrated noble killer into a hash of referencing, smashed together in a manner that is, I think, genuinely countercultural, because the mode of composition exhibits no respect for the military, for beauty, for the religious ecstasy of crowds, for empires.

Looking at that posse of pantomime idiots touting their stupid props, these mismatched fools glorying in their own placelessness, these ciphers glued together from car boot salvage, I don’t get a sense of masculine empowerment, a feeling of being swept up into an imperial brotherhood of righteous loathing and suspicion. Instead, I see an ethos of self-deprecating abandon and above all, an embrace ofdisparity, with the things Space Marines are now known for - patriarchal rage, absolute dominion and destruction - reduced to gaudy foreground elements, picked up and brandished like toys. I don’t like these figures in the way that Saber Interactive would have us empathise with Titus and co in Space Marine 2, but I am curious about them. I’d like to know where they’re going.