HomeFeaturesLlamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story

Why did Digital Eclipse make Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story? It’s a tale of centipedes, psychedelia, and teaEditorial director Chris Kohler explains why they decided to preserve the work of the legendary British solo dev

Editorial director Chris Kohler explains why they decided to preserve the work of the legendary British solo dev

Image credit:Digital Eclipse

Image credit:Digital Eclipse

Who is Jeff Minter? Unless you’re a long-term fan of his work, you might have asked that upon hearing aboutLlamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, the latest interactive documentary from Digital Eclipse (following on fromThe Making Of KaratekaandAtari 50: The Anniversary Celebration). You might have heard Minter’s name in connection with the remake of the unreleased Atari arcade game Akka Arrh in 2023. Maybe you played his mind-warping shooterPolybiusin VR. You might remember as far back as the Atari Jaguar and Minter’s phenomenal Tempest 2000, the unexpected highlight of the console’s library. Or perhaps you recall his work from the 8-bit glory days. You could just know him from the daily videos of himfeeding his sheep on YouTube.

The point is that Jeff Minter has been making games for a phenomenally long time – more than 40 years, in fact. And in all that time, he has stayed true to what he believes in. “One of the things we say in the game itself is the idea of him being the last indie developer,” says Chris Kohler, editorial director at Digital Eclipse in California. “The last of the people from the early 80s who very consciously never sold out, never took the money, never looked to expand or do anything other than [be] just Jeff at his computer, making the sorts of video games that he wants to make.”

“There’s very few stories like that, there’s very few people like that, who have been doing that for 40 years,” he continues. “I’m struggling to think of another one. There are people who are still in games, but they progress up the managerial ladder, or they open up a studio, or they end up doing something else. Just to have somebody that started in 1980 just sitting there programming games, and who’s now still sitting in front of his computer programming games, it’s a very, very unique situation.”

Image credit:Digital Eclipse

Image credit:Digital Eclipse

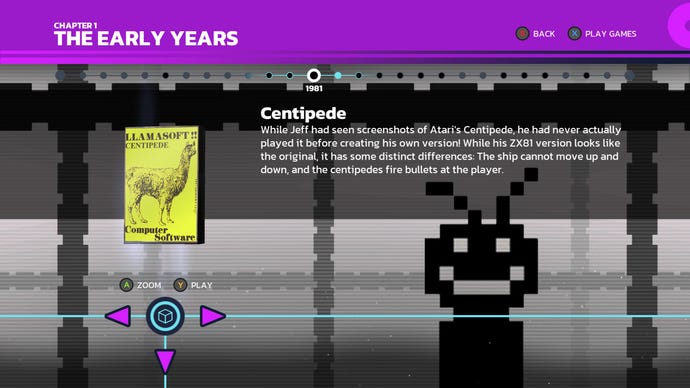

Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story finally gives everyone the chance to play through Minter’s back catalogue, going right back to the days of the Sinclair ZX81. But perhaps more importantly, it provides context for each game through video interviews, photos, quotes, magazine articles and even issues of Llamasoft’s newsletter, The Nature Of The Beast. Kohler thinks that this context is essential: “When you learn about what he was doing with each of those games, you’re going to have more of an appreciation for it when you actually play it,” he says.

Image credit:Digital Eclipse

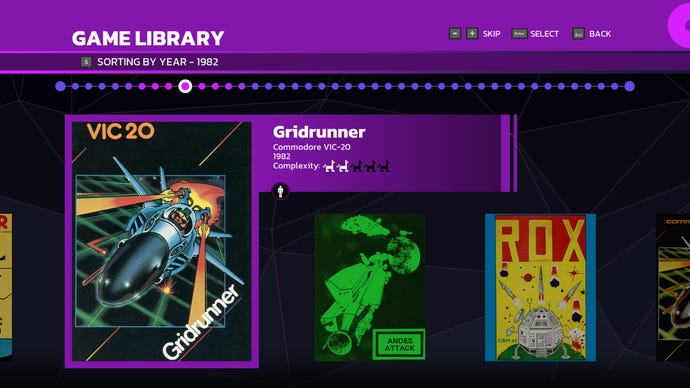

Gridrunner from 1982 is the first truly great game in Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, although far from the last. Titles like Attack Of The Mutant Camels and Ancipital were wildly inventive, with each release invariably featuring llamas, camels or various other ‘beasties’ in some shape or form. You always knew when you were playing a Jeff Minter game. The mid-80s also saw the release of Psychedelia for the Commodore Vic-20, the first in a long line of ‘light synthesisers’. Minter explains in a video that he would often envisage abstract moving shapes in his head, and these light synthesisers were a way of representing that, featuring trippy patterns that could be manipulated in time to music. Minter would later go on to create light synthesisers for systems like the Jaguar and Xbox 360.

The missteps are arguably just as interesting as the triumphs, however, and the in-depth discussion of Mama Llama in particular is fascinating. It’s a vibrant, experimental game that sees the player defending a family of llamas from attack, and it divided critics at the time. There’s a candid interview where former Zzap!64 journalist Gary Penn defends his withering review - a review that Minter seems miffed about to this very day.

Minter also seemed to have an almost unerring knack for backing the wrong horse. In the late 1980s, he invested in an expensive development kit for the Konix Multisystem, a British console that could be configured with a steering wheel, flight yoke and motorbike handles. “This was going to be the UK’s home team advantage, as it were, for a gaming machine,” says Kohler. “Japan had Nintendo, America had Atari, and if you were British video game developer, this was going to be the one that was right in your backyard.” Minter was developing Attack Of The Mutant Camels ’89 for the Konix Multisystem when the console hit the buffers, and neither the game nor the machine saw the light of day. But thanks to a group of dedicated fans who were able to put together a Multisystem emulator with the help of the game’s source code, Attack Of The Mutant Camels ’89 is now playable as part of this Digital Eclipse collection.

“He went from the Konix Multisystem and then he said, ‘OK, all right, well, that was a big failure, so I’m gonna make games for the Atari Panther,” says Kohler of Minter’s ill-fated journey. “And then after that, it was, ‘OK, I’ll do the Atari Jaguar’, and then the Nuon, and then the GameCube, and he always seems to have this uncanny ability to just go right for the underdog. But ultimately that’s Jeff, and that’s that independent streak, where he’s not just gonna follow the crowd.”

The Konix Multisystem debacle represents the start of the Act 2 of Minter’s life, the point where, after years of widespread acclaim in Act 1, things start to fall apart, and it became increasingly hard for Llamasoft to remain independent. “In the 90s, he was fighting against the increasing commercialization of the video game industry,” says Kohler. “In 1981, he was on a level playing field, because practically everybody was just copying games to cassette tapes, and you can get distribution into retail channels that way. But around that time of Llamatron, he found that the doors were now closed to him in many ways. The cost of entry, the cost just to play in the video games industry had skyrocketed, and as that realisation came to him, he had to figure out, ‘How am I going to compete?’ So he decided to try shareware and see what happens, and the Llamasoft fans come in and they bail him out. They sent him the five pounds he was asking for, and some sent him even more than that.”

Image credit:Digital Eclipse

This sets up the triumphant Act 3, where Minter receives widespread acclaim for his reimagining of the Atari coin-op Tempest for the Jaguar. “The endpoint of our story represents everything that Jeff was doing all kind of coming together,” explains Kohler, “like his love for Atari, his love for arcade games and shooting games, and also his love for that sort of visual denseness, richness and complexity, his love for musical visualisers. Because that’s kind of what Tempest 2000 feels like: it’s a marriage of shooting gameplay and trippy psychedelic music visualiser.”

Kohler says that Digital Eclipse decided to stop at 1994’s Tempest 2000 partly because it felt like a good resolution to the story, but there were also some practical concerns with including Minter’s later games, such asSpace Giraffeon the Xbox 360. “We wouldn’t have been able to emulate them or integrate them into our engine, basically,” he says. “Tempest 2000 is not quite totally topping out the capabilities of what we can do in the Eclipse Engine, but it’s getting there.”

Nevertheless, a timeline is included that includes every title for reference. “We do have the complete list of everything that Llamasoft released, even licenced stuff that we couldn’t include,” says Kohler, “So you can quickly go down and look at screenshots of everything, including the impossible-to-play-now iOS games that he that he did.”

Image credit:Digital Eclipse

Still, Kohler’s outsider perspective did result in one hiccup during development. “We sent Jeff the first build where he could really look at the timelines,” recalls Kohler. “I was prepared for him tocome back with ‘this is wrong, that’s wrong, that’s out of order, I don’t think this’, with all kinds of things. And I literally got one substantive comment from Jeff, one comment from him that was something that was wrong and needed to be fixed. And it was I had taken a public domain image of a cup of tea. And he has like, ‘This tea is absolutely wrong. The tea bag is still sitting in the tea, which we would never do in Britain, and there’s no milk in this tea. It is completely un-British’.”

Kohler sent methe original public domain imageof this cup of tea, and I agree with Jeff that it’s a complete abomination. But thankfully the offending drink has been removed: Kohler went to great lengths to ensure the tea image in the final build is as British as possible, even ordering a Union Jack mug from Amazon along with some PG Tips, and picturing it next to a Commodore 64.

Who is Jeff Minter? He’s a legend.