HomeReviewsShadows of Doubt

Shadows Of Doubt review: a buggy yet brilliant detective sim of grand ambitionCriminally good

Criminally good

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Fireshine Games

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Fireshine Games

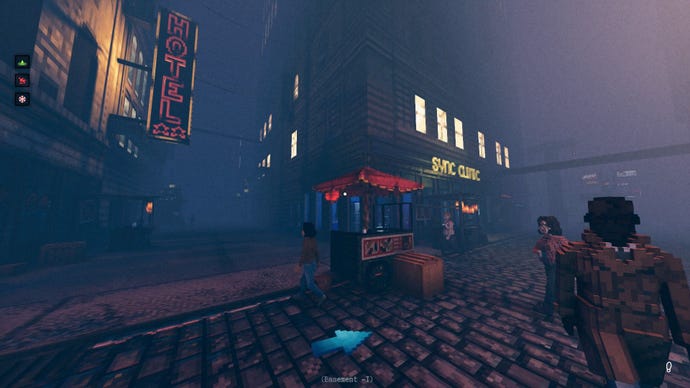

For years, a dangerous and charismatic game has evaded the grasp of many designers. Some say it doesn’t exist, that no publisher would ever back it. I’m talking about theone city block RPGthat Warren Spector has often mentioned. Sure, we’ve seen a few usual suspects already -Deus Ex Mankind Divided,Disco Elysium, evenElse: Heart.Break- they all grimace in the line-up but nothing ever sticks. Now, out of the gloom of indie development, comes another perp ready to have his mugshot taken.Shadows Of Doubtis an open world detective sim that comes perilously close to being our guy. Its clothes, stature, gait, and fingerprints match the description of what Spector often describes. And yet, if you tilt your head, something is just a little off. The game isn’t confined to one block. It’s not an RPGprecisely. And its simulation has plenty of bugs, jank, and unintentional comedy. But after all this time, in the absence of a smoking gun, shouldn’t we just put this guy in the slammer and call the case closed? I say yes, let’s. Officers! Arrest this game, it’s brilliant.

Shadows of Doubt - 1.0 & Release Date Announce TrailerWatch on YouTube

Shadows of Doubt - 1.0 & Release Date Announce Trailer

You play a private detective who walks the streets, sometimes accepting small time investigations (side quests) to recover lost items or find missing persons. But mostly taking on longer murder cases. Bodies are often found in their own apartments and it’s up to you to find out what happened.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Fireshine Games

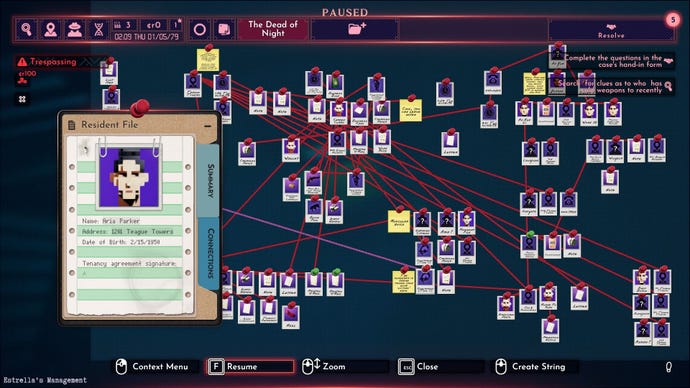

Even to “resolve” a murder, you have to fill in a form at the city hall. You’re asked for the name of the killer, their full address, a credible murder weapon, and proof they were present at the scene of the crime. This is the information around which your investigations orbit, the essential ingredients of a cracked case. It reminds me of board games more than video games, sharing the objectives of Cluedo, and the piecemeal information gathering of Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective.

So, a game of blood and paper. Sounds quite orderly as murder mysteries go. Perhaps it is, for some detectives. In my experience, as detective “Dick McClumps”, it’s often a wonderful Coen brothers farce.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Fireshine Games

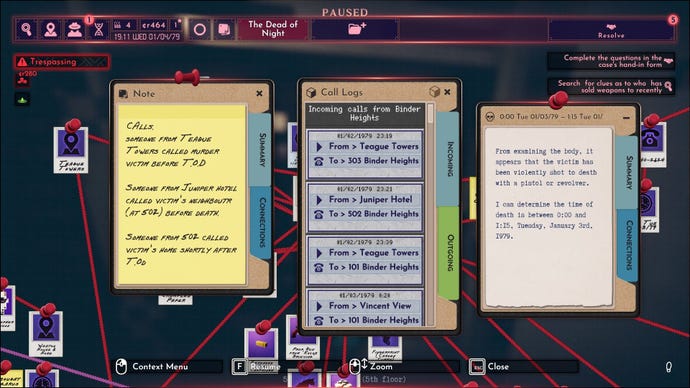

My first case saw me visit a luxury high rise, where I was marked as “trespassing” just for dripping my raincoat on the marble hallway (you can get fined if you’re caught). I was in a haste to gather dirt on a person I suspected of buying a weapon on the black market. In my hurry, I broke into the wrong apartment. The suspect was next door. “That’s okay,” I thought as I realised my error. “There’s a vent shaft in this closet. I’ll adopt the usualimmersive simtactic, and crawl next door via the air ducts! Hah!”

Experientially, this whole sequence - a result of the game’s intertwining systems and commitment to simulation - was more interesting, funny, and unique-feeling than many first-person explorathons I’ve played in recent years. And all I did was pick the wrong lock and get lost in a vent. In terms of “emergent gameplay” Shadows Of Doubt is an incredible toy. It also fits into the quiet trend of “knowledge-based” games that encourage active learning as a means to progression, as opposed to “hey, you can double-jump now!” (Although there are biomechanical skill upgrades you can unlock).

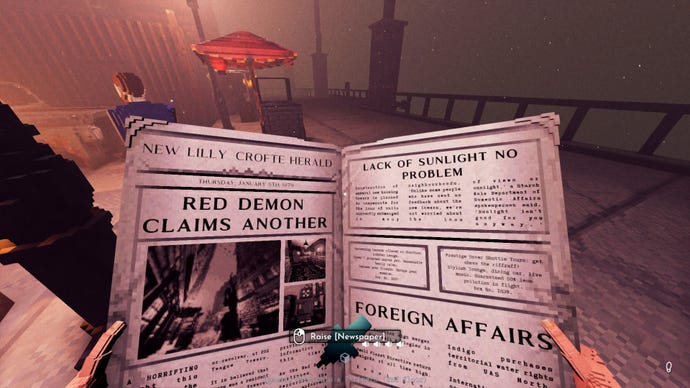

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Fireshine Games

That particular case ended in a round of fisticuffs - a rudimentary biffing mechanic that was absurd and hugely entertaining, yet definitely a type of movement the game doesn’t feel well-suited to. Inventory management and item use is likewise a fiddly, game-pausing affair of pill-swapping and lots of clicking on “drop/place” with inaccurate results. These foibles didn’t bother me so much, but I know it’ll drive some people up the wall. I only appreciated how the limited inventory space would force me to make silly choices. At one point, I threw a revolver I’d confiscated into the river, just so I would have room in my pockets for a newspaper (you can use it to hide your face and it sometimes contains information about the murder cases you’re on).

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Fireshine Games

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Fireshine Games

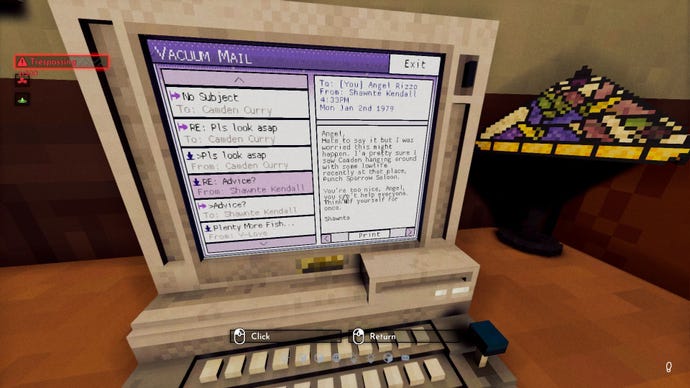

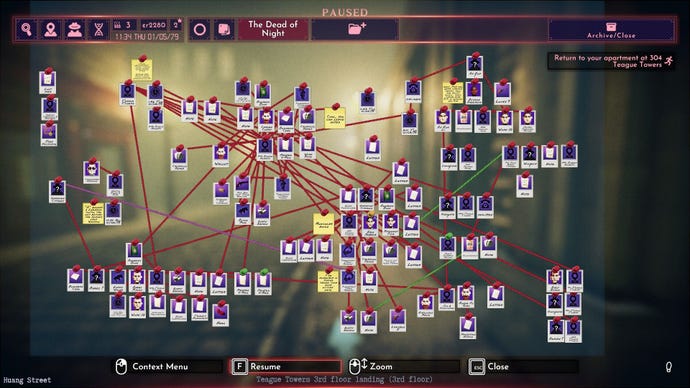

Some will fairly consider such jank a flaw in the simulation. Anyone complaining that 1.0 still feels a bit “early access” is justified. But, having smiled or laughed at many of the oddities, I feel many flaws are also part of the game’s ambitiously layered texture, the price to pay for a deeply complex and truly emergent game. You will run up against the limitations of the game’s world, absolutely. Emails will repeat, you will see patterns and murder types emerge, as if finally noticing a texture tiling into the distance. But for a game to be as anecdotally rich as this, I can forgive the repetition, the sight of its seams.

For a closing example, take chatting to NPCs. It’s a classic case of dialogue being more or less identical for every person in this world. You’re offered the same menu of questions to put to every person, and usually get the same variety of bottled, non-descript responses. This rings a bell.Mount and Blade’s dialogue was similarly systematised, a vaguely human set of sentences and concerns that repeated themselves across all cultures and characters.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Fireshine Games

Just as I clicked through those samey menus seeking marriages and mercenaries, I eventually accepted the identikit witness testimonies of these cyberpunk citizens. Yet what I happily accept as a systematic (and funny) punchcard of chit-chat may snap the atmosphere in half for other players who crave a greater sense of humanity. The monolithic voice of the citizens can be an alienating force, a reminder that this is a machine, a sim, and not a living place. This is probably not the “one city block” game Warren Spector sorely seeks to detain, in other words.