HomeFeaturesLike a Dragon: Infinite Wealth

Like A Dragon’s localisation team explain how they bring the series’ singular storytelling to the west“We love kink-based wordplay here at Sega”

“We love kink-based wordplay here at Sega”

Image credit:Sega

Image credit:Sega

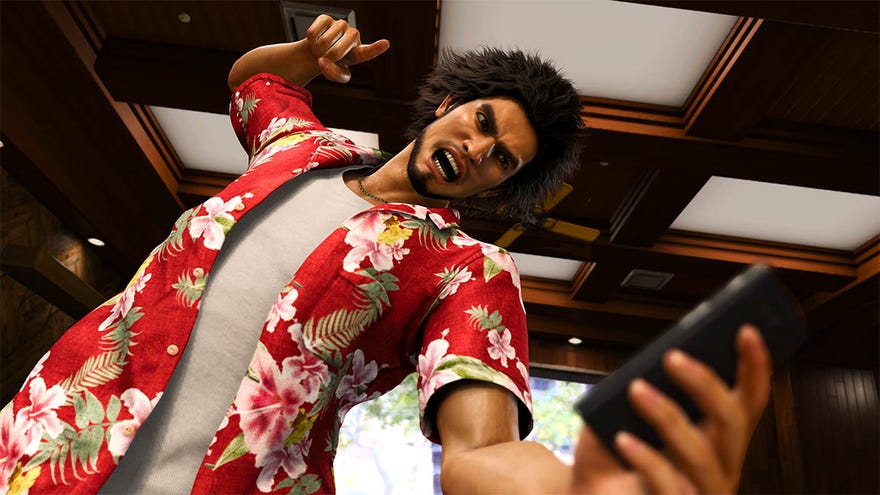

“Ever since the very firstYakuzaon PS2, the Like A Dragon series has always tried to capture the cultural zeitgeist of Japan, reflecting and satirising whatever’s trending around when the game comes out. This means that the way people speak in Like A Dragon is constantly evolving to match the times,” says Dan Sunstrum, senior translator at Ryu Ga Gotoku’s localisation team. Keeping things current is, says Sunstrum, “a challenge in some ways but also means we’re justified in using modern English slang to match, whereas such modernisms might feel out of place in a game set in a completely fictional world.”

Conversely, says Sunstrum, some of the trickiest words to localise are the common ones, since each instance generally needs a creative solution to fully capture the context it’s used in. “One of these words for me personally isamaeru, a verb that has no direct translation in English but which I will roughly describe as ‘acting in a way that communicates that you want someone to take care or dote on you’.” It’s usually used for scenarios like a child asking a parent for a piggyback or a treat, “but is also versatile enough to be used for decidedly adult characters like Kiryu.”

He gives a simplified example of how the process might work from start to finish:

Japanese:ちゃんと仕事してくれりゃチップもはずんだのによ。悪りぃが金は払わねえぞ。……封筒、返してくれや。

Translation: If you’d have done your job right, I would’ve given you a generous tip. Sorry, but now I’m paying you nothing… And give me back my envelope.

Edit:Y’know, if you just did your job, you’d have got a fat tip. But now all you get is a fat lip. Oh, and gimme my envelope.

“This is right after Ichiban fights Tomizawa, a crooked cabbie who attempted to rob him at gunpoint. Does the Japanese line mention a fat lip at all? No. Does the English line still convey the same information while respecting the scene, the characters, and the creators’ original vision? Absolutely.” He continues, “it conveys that Tomizawa’s not getting paid a dime, and is logically consistent with Tomizawa’s slightly bloodied, beaten-up state. Could Ichiban just as easily have said, “But I ain’t payin’ you shit now” in his usual crass way? Sure, but he would’ve sounded like any other trash-talking thug, and this is one of many moments that highlight that, among all the street punks and underworld goons he blends in with, his charisma alone is enough to set him apart.”

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Sega

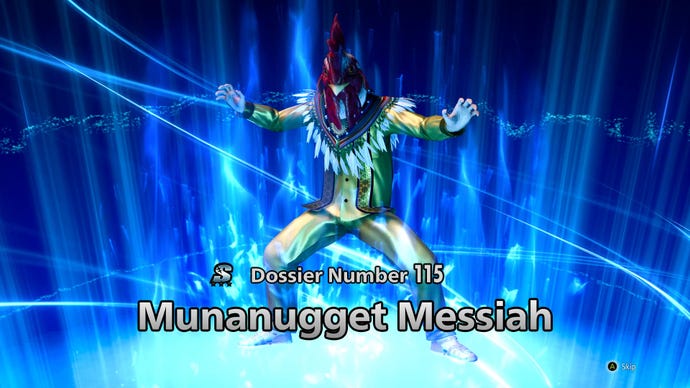

Malone says a good example of this is the ‘evolutionary line’ for the lubed-up enemies in Ijincho. “In Japanese, you’ve got Lotion-Lathered (ローションまみれ), Lotion-User (ローション使い), and King Health (キングヘルス), ‘health’ in this case meaning ‘men’s health’, a euphemism in Japan for erotic massages. Nuanced, no?” Playing the game in English, you’ll encounter these Sujimon as City Slicker, Grease Monk, and Pornogra-Pharoah. “The first two enemies based on slipperiness, the final enemy based on pervert status, just like in Japanese. Kudos to our lead editor John Moralis for divining these strokes of brilliance; we tend to pull him off whatever project he’s on for this specific purpose.”

Given that Ichiban’s imagination is so deeply rooted in the Dragon Quest series, says Malone, the team often use those games as a guidepost. “Dark Santa/ダークサンタ becomes Krass Kringle. ImplantOgre/インプラントオーガ becomes Modgoblin. Needleraiser/ハリ・レイザー becomes Weltraiser.” The Needleraiser is a perfect example, says Malone, since ‘needle’ in Japanese is ‘hari’. It’s “phonetically similar to ‘hell’, and once you see the Sujimon in question, you know exactly where the inspiration came from.”

There are definitely moments though, says Malone, where a joke or culturally specific reference can leave the team deliberating how to render it in English. This becomes especially interesting when slang terms are involved. Malone gives the example of the opening scene of Lost Judgement. The hero, Yagami, is tailing a college kid who heads into a mysterious room referred to as “shikinoma” (しきのま). Yagami overhears this, so without actually reading the kanji, the meaning remains ambiguous.

“Well, a betting man would say he’s gambling. If it’s a members-only building with goons posted on every corner… I’m telling you now, the tatami room ain’t no tea shop.”

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Sega

“We could’ve played it straight, but we decided to read between the lines here and look at the purpose of the dialogue,” says Malone. “What we really needed was a clue about this room that wouldn’t break immersion, something our audience would recognize.” They settled on ‘tatami room’, which are still “fairly ubiquitous” in Japan. The word might also conjure a tea ceremony, “Another Japanese custom known worldwide.” Of course, says Malone, “a cho-han parlour might also utilise tatami to preserve that traditional feel, but again, only a gambler (or an ex-yakuza) would know something like that.”

It’s not only this sort of streetwise awareness the team have to be cognisant of with many of their characters. On top of regular colloquialisms, there are also region specific, and even yakuza specific terms and dialects.

“The yakuza do actually have a good deal of slang/jargon they use – at least in fiction; I’ve never talked to a real one,” says Sunstrum. “When coming into the Like A Dragon series for the first time it takes a bit of time to onboard these terms if you weren’t familiar with them already.” Sunstrum gives some examples: ‘Katagi’ is “someone who is not part of the yakuza; a civilian. Literally ‘upstanding person’,”; ‘Mikajime’ is protection money, literally ‘management/oversight’; ‘Shinogi’ is “a source of income, usually through dubious means; a racket,” literally, ‘something you do to endure hardship’.

Fans ofYakuza 0will know that the story frequently switches between Tokyo and Osaka, the latter of which has its own distinctive dialect, called Kansai. “The most important thing about rendering a dialect is replicating its ‘flavour’ or ‘character’ in English in the same way it might be perceived in Japan,” says Malone. “For instance, Osaka dialect tends to be fast-paced and flamboyant while Hiroshima dialect tends to be slow with a country twang, though how exactly this comes across varies from person to person. We have style guides that lay out the details on how to achieve a baseline for these dialects in terms of word choice and grammar.”

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Sega

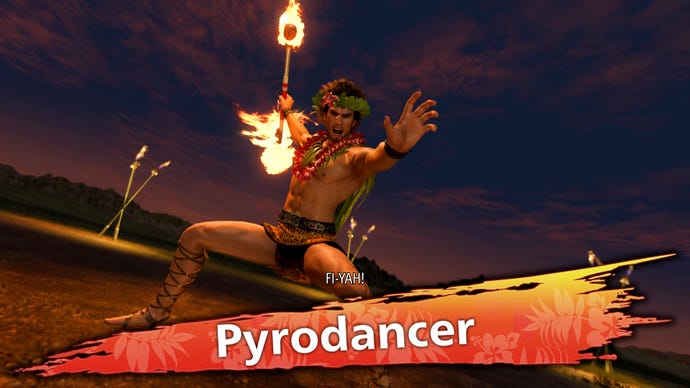

It’s impressive to think about the huge chain of talent and disciplines that even a single line goes down before it gets to us. Of course, it doesn’t end with the page. “As for Japanese-speaking Hawaiians, their Japanese resembled the usual Tokyo dialect – it’s the Hawaiian Pidgin and ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi that we endeavoured to replicate. This could not have been done without the input of our voice acting talent in Honolulu, whose adaptations of the original script resulted in a vibrant mix of expressions that faithfully represents the local sound.”

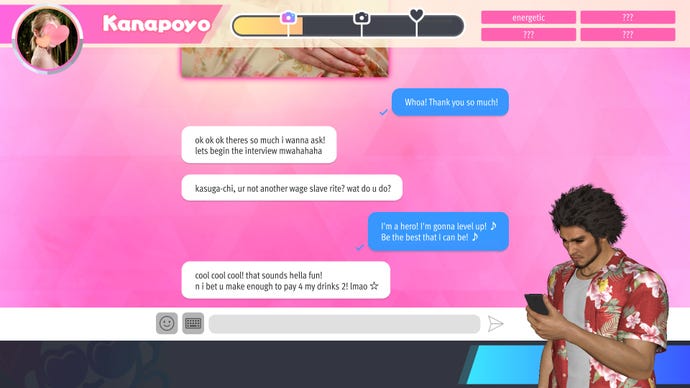

Wherever the series ends up going next, though, both Ichiban and the series’ tributes to the medium of games itself likely won’t be far behind. “One example that comes to mind is the phrase 成り上がる (nariagaru), a single verb which when translated comes out to the wordy “to move up in social status,” says Sunstrum. “This phrase comes up a few times in Yakuza: Like A Dragon, notably the scene where Kasuga shares with Nanba his childhood dream of becoming a hero.” This scene, however, had strict timing requirements, so to convey this without getting overly wordy, “we drew a comparison between moving up in life and levelling up in a video game.” It’s something they were only able to pull off because of all the Dragon Quest references.

“We ended up using the same localization in Kasuga’s karaoke song, The Future I Dreamed Of. The chorus starts with “nariagaru ze”, which became ‘I’m gonna level up.”