HomeFeatures

How the checklist conquered the open world, from Morrowind to SkyrimThe first in a new interview series about a sprawling, exhausting genre

The first in a new interview series about a sprawling, exhausting genre

Image credit:Microsoft

Image credit:Microsoft

There’s no genre like the open world for inducing choice paralysis, so it’s fitting that I’ve been agonising over how to begin this irregular article series onopen worldgames for months. I have a lot of material, oodles of interviews with developers of all shapes and sizes - big shops like Remedy and CD Projekt, smaller studios like Ace Team and Awaceb, all holding forth on such topics as whetherElden Ringor Zelda did bandit camps better, and how you make a forest feel endless. There is so much you could talk about, so many trails heading off in all directions, but perhaps it’s best to begin with the more personal and superficial question that inspired this investigation: how did the open world game get soboring?

Image credit:Eurogamer / Ubisoft

This is a commonly heard criticism of the genre today, and not just from reviewers who have to write up these enormities for embargo.

As to why open worlds have lost that element of surprise, Purkeypile points straightforwardly to how expensive today’s biggest games are to make, and the number of people involved in their creation. There has never been greater pressure to standardise the format and mitigate the risk of a flop. And the larger the team, the harder it is to set aside time for explorationwithinthe complex geography of video game development.

“When you have literally thousands of people working on the game, sometimes you need to be able to have these bite-sized portions of ‘do this, go there’,” Purkeypile says. “It’s very hard to run things at that scale without all those checks and balances and stuff.”

Purkeypile contrasts this with his memories of working onSkyrim, back in the noughties.

“We were like 100 people back then, and there were lots of trust in the team, where you could just take something and make it your own. Like Blackreach - that was not on the schedule at all. We did it as a skunkworks project on the side, and people saw it and said, oh, that’s really awesome - I guess we should keep it. And I have people, to this day, say it’s one of their favourite things, because they go into that deep, dark dungeon to find something we never tell you about. It’s like, vaguely hinted at, but it’s a surprise.”

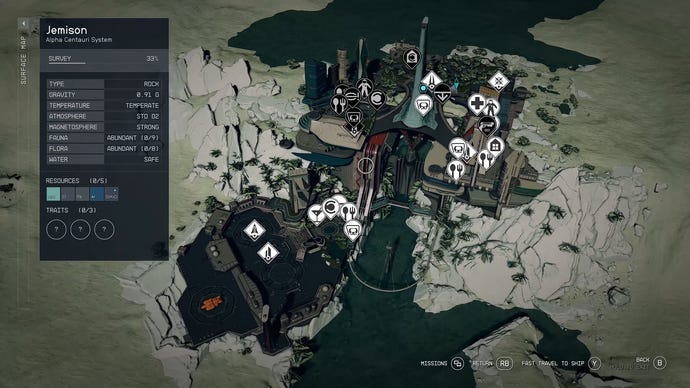

Purkeypile left Bethesda partly because there was less opportunity for such trips into the undergrowth during development ofStarfield, which Alice B (RPS in peace) pithily summarised as beingso big it feels small.

“Starfieldwas like 500-ish people across four studios,” Purkeypile says. “I think there is still a lot of individual storytelling there, within spaces, and cool places to find, but it is definitely harder at that scale.”

Image credit:Bethesda

“If you play that right now - there is no compass, no map, literally the quests are like ‘go to the third tree on the right and walk 50 paces west’,” Firor says. “And if you did that now, no one would play it. Very few people would play it. So now you need to give them hints and clues, and because nobody wants to really devote that much time to problem solving. Like they want to go and be told the story, or enter or interact with another player, or interact with an NPC.

“Morrowind is a great game obviously,” he goes on. “It’s one of my favourite games. But the way it told its story with the open world is a little out of date for the type of gamers that we have now, where they’re not all hardcore, they’re not all PC or generation-one console diehards, right, who are going to go out and invest as much time in the game as possible. Now [that there are] so many other options for players, you really want to make sure that it’s engaging and fun, and wandering around a field trying to gauge 50 steps from a tree is not part of that anymore. Which is kind of sad, because I’m old school.”

Image credit:Microsoft

One reason to preserve that touch of Morrowindy ambiguity is simply that developers love seeing players embroiled in the act of actually working something out, tracking something down. This is, Firor suggests, the fundamental appeal of devising an open world game, the emphasis that differentiates it from other genres.

“It’s make a space and then just populate it with things to do, and the players can do it in any order. And sometimes it’s a little chaotic. And sometimes you can’t figure out what the players are going to figure out, because they’re smarter than you. But that’s what the world is like too. And it’s so much fun, just to create space and let players into it, and then see what they do.”

I’m hoping to take a similar approach with this article series: make a space, and see what you all do within it, which overgrown paths you lead me down. Partly, this is a gesture of armchair designer resistance towards one of the fundamentals of open world design, the tendency to have that world turn on the movements of a single agent. But also, as Firor says, it’s just fun. I’m hoping that you’ll join me on this trek, and give me some headings.

Image credit:Take-Two Interactive

We could explore the more famous open world landmarks, such as the infamous towers of Assassin’s Creed, which began life as a means ofnarrowing the divide between player and designer. We could devote pieces to individual games - not just yer Skyrims and yer Grand Theft Autos, but lesser-known, discreetly influential oddities such asThe Abbey Of Crime, or mods such asBrookheights, an unofficial open world expansion ofThe Sims. We could investigate open world memes, like the urban legends that haunt San Andreas. And bubbling beneath all that, a cauldron of more diffuse thoughts about the philosophy or poetics of open worlding. How should you aestheticise size and open-endedness for their own sake? How do you characterise the player of an open world game - invader, explorer, wanderer, vagrant, collector, saviour, trespasser, woman, man or none of the above? What even is a “world”, anyway, and what really distinguishes an open world from a closed one?