HomeReviewsDragon Quest III HD-2D Remake

Dragon Quest III HD-2D Remake review: a world in the palm of your handA model village the size of a medium-sized country

A model village the size of a medium-sized country

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Square Enix

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Square Enix

Dragon Quest III HD-2D Remake’s premise is bluntly, delightfully simple. The Archfiend Baramos, as evil as he is mysterious, is up and about. He’s got ill designs on the world. Your Dad tried to stop him, and he died. He fell into a volcano. We absolutely can’t be having that.

This is, more than anything else, a game about Going On An Adventure. Well walked ground, of course, but it’s rare to see it embarked upon with such barefaced delight, or such a wholehearted commitment to going the distance. It is a very big and a very simpleRPGthat is as wide as an ocean and as deep as a pond; a game to curl up with and play lazily and—with some sour caveats—enjoyably, for an entire winter.

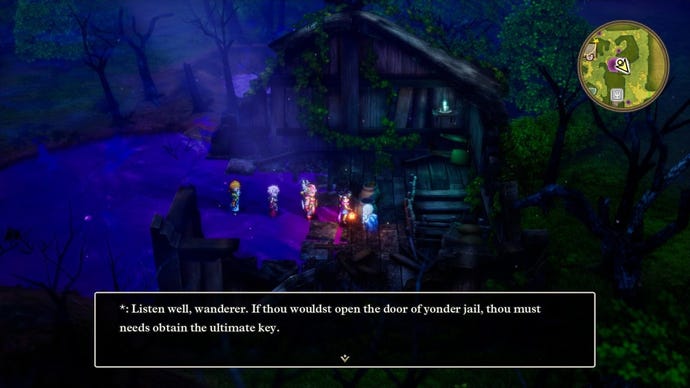

After nearly three decades of remakes and re-releases since its 1988 debut,Dragon QuestIII arrives, tilt-shifted and glimmering, in Square Enix’s HD-2D. This approach (first appearing in 2018’sOctopath Traveler) combines 2D sprites with a detailed 3D world and—with a combination of camera tricks, simulated lenses and intricate lighting—renders out the world into a kind of toy-like diorama. The overall impression is that of looking down into a model village the size of a medium sized country.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Square Enix

This breezy approach to the mechanics, items, and MacGuffins of your quest to save the world runs like a breath of fresh air throughout the game. Much of the first few hours are taken up on a hunt for keys, graduating to stolen crowns, a bottomless pot, keysagain, and a pinch of pepper to season a king’s dinner. Even when the items invariably trend towards the fantastical and the stakes get higher, this playful, almost dreamlike tone persists. There’s a kickabout feel to it all, like a playground game. One old man is every old man; the bruiser in the tavern is the bruiser in the square is the bruiser standing on the dockside. This could become formulaic or repetitive—and it is, a little—but what’s being asked of you isn’t being repeated: just the guises and tones of the people doing the asking. Find the waking powder to free the sleeping village. Defeat the serpent monster. One task splinters off into the next, another little king gives you a quest so straightforward as to be almost elliptical.

The squashed Earthlike approach extends beyond the landmasses. As soon as you emerge into the vast main map you start running into direct analogues. Romaria is obviously, glaringly, Rome. Portoga stands in for Portugal. Ibis is very clearly ancient Egypt. Each of these towns is intended as a broad, smiling caricature, but the smile is just a little too wide to hide several rotten teeth. I find it hard to object to the city of Edina’s caricature of Britain as a manners-obsessed, stuffy aristocracy, but as the game moved into Asham (so taking its name from the Arabic greeting “as-salamu alaykum”) complete with bottom-of-the-barrel tropes of spices, belly dancers and night markets, my heart sank.

And, for the most part, the character sprites are all the same wherever you are. The shopkeeper in Romaria is the same as the shopkeeper in Asham, as is the old man (white hair, blue robe): White, smiling sprites speaking in a broad dialect of whatever caricatured city you find yourself in. This is racist, ugly stuff and isn’t the only instance where the game’s thoughtlessness bubbled up, sour and imposing. When I encountered an enemy type called “Heedoo Voodoo”, a racist-children’s-book cartoon of an African tribesman, I turned the game off for the rest of the night. It wasn’t the last time I did that. Things like this would have stood out in 1988 and it’s remarkable that they weren’t altered or addressed with a remake that is already clearly so invested in altering the game’s visuals and presentation.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Square Enix

Travelling from one town to the next, your party is gigantic in the overworld. Forests foam up around your ankles. Outside the safety of the towns, and in the game’s enemy filled dungeons, you’re constantly tumbling into random encounters. There is no indication as to where these enemies are—no “tall grass” or warning—and in the early game I found this almost intolerable. At that point battles took time, even with the granular auto-battle switched on, and while I could have fled I desperately needed the experience to help me fight other, more troublesome foes.

In the game’s dungeons I grew to resent the random encounters especially deeply. I wanted so badly to explore, to dive down a beautifully rendered side path, but each encounter felt like an interruption, a wagging finger, a patronising “Ah, wait—”. My frustration reached its nadir as I discovered (O, delight!) an item that purportedly prevented random encounters only to learn (O, horror!) that it had no effect at all within the dungeons.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun/Square Enix

Maybe you think that when I say “wide as an ocean, deep as a pond,” I’m damning this game with faint praise. I’m not. Listen to me—listen to me—the ocean is very,verywide. I could spend the whole review listing things that are in the game, context free, and I still wouldn’t make much of a dent. Little mechanical wrinkles ripple through the game. You start exploring the world in new ways. You’ll find villages tucked away in areas you thought you’d explored. On several occasions, the breezy, single-minded arrow of the game’s main quest goes splintering in a variety of directions simultaneously and you start to pick and choose what to approach next. There is a real joy in cutting about the world with wild abandon, neatly closing the loop on one fantasy peril after another.

It is tough to imagine a better match for this game than the HD-2D art style, with its pristine dioramic effect. There is a tendency in remaking older games to reinterpret them through the prevailing, marketable art style of the moment. It would have made sense from a business perspective to take a game as beloved as Dragon Quest III and present it more like Dragon Quest XI: pop it out into full 3D, fill out a quest log, write individual stories for each party member. Instead, Dragon Quest III and the HD-2D style make perfect bedfellows: a sprawling, kickabout, shaggy dog story of a game rendered out like a model railroad: at once impressive in its scale and intricacy and charming in its jewel-like miniaturisation.

You could start playing this today, an hour at a time before bed, and you’d still be playing when the snow melted in Spring. Some portions of that adventure are better than others. Some are downright ugly. With those caveats, in its latest (and possibly definitive) incarnation, Dragon Quest III is a colourful, adventurous romp of wild goose chases, indistinct but compelling rumours, and tactical positioning: a miniature fantasy made grand.