HomeReviewsCaves of Qud

Caves Of Qud review: an obscenely rich roguelike realm you could get lost in for monthsA goat approaches

A goat approaches

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

Caves of Qud 1.0 - Official Announcement Trailer, with Kitfox GamesWatch on YouTube

Caves of Qud 1.0 - Official Announcement Trailer, with Kitfox Games

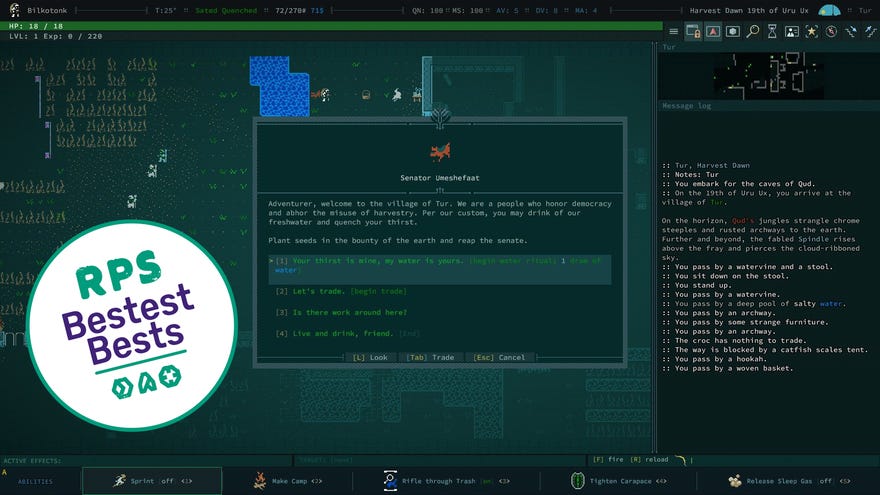

That said, if you’ve not played many classicalroguelikesbefore, it may still appear intimidating. You can play with the mouse, clicking on locations you want your character to go, and navigating menus with taps of the cursor, but it’s really designed to be entirely keyboard based, clacks of the numpad and plentiful hotkeys summoning to mind days when mouse pointers did not even exist.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

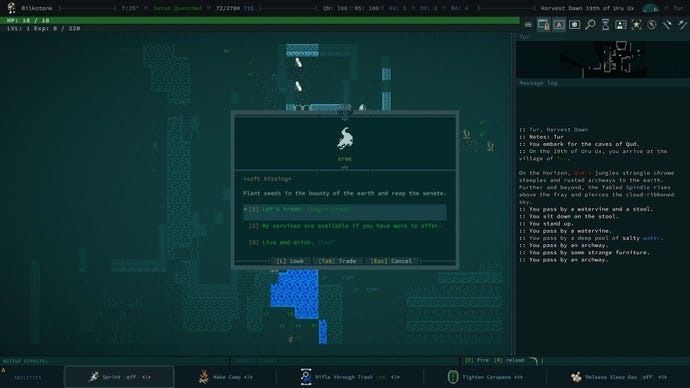

In that life, I was playing as a quill-covered, multi-limbed spiderfreak I named “Borkubine”. You can create your own character, see, mixing and matching an astounding array of abilities (or you can choose from a bunch of presets). I was also making use of the forgiving checkpoints in “roleplay” mode, which let you treat any village as a save point. But in “classic mode”, Qud is more unforgiving and traditional - no skills, items, or riches are carried over when you die, and there is no save-scumming. True to roguelike form, you perish and that is that. You come to value your sharpshooting skills, your investment in armour, or a love for your tactical bubbleshield. Then, in a single lapse of attention, all those shiny upgrades and special weapons are gone.

It elicits a state of tense freedom. In one sense, classic mode makes you want to cling to your fragile life, even if it means acts of bullet-dodging desperation. But seen from the perspective of a nothing-to-lose Rogue diehard, you will find existential liberty in re-rolling a random character just to experiment with new toys and the game’s many “mutations”. (The “Daily” mode is the perfect extension of this, offering the same random start to every player.) Let’s see, what do we have this time? Slime glands that’ll spit toxins? Pyrokinesis? Or perhaps something called “Quantum Jitters” - a defect which will periodically tear space and time accidentally asunder. As lucky dips go, it is a violently exciting assortment of treats.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

For those disinclined to pimply lore, the reliance on reading messages to set the scene may test the attention span. But I feel like Qud’s appearance will already have scared away anyone with a lack of patience for the BBC Micro baroque. It is not really ASCII art, but it does feel ASCII-inspired, the tiny 16x24 pixel sprites sometimes resembling ancient undeciphered hieroglyphs instead of fully realised birdfolk or vine farmers. It is a kind of book-reading magic that Qud does, outsourcing all the heaviest graphics to the player’s brain.

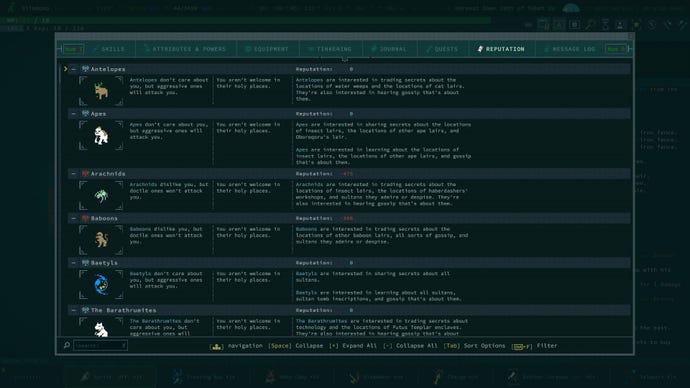

And anyway the actual text is a great example of otherworldly video game language. The kind that has evolved separately to mainstream action adventures with all their cinematic dialogue. “Worms are interested in hearing gossip about them,” you’re told in an exhaustive menu that tracks your reputation with everything on the planet. “Crabs dislike you… You aren’t welcome in their holy places.” There is an expansive and austere comedy in any game that will track your reputation with just about every type of being from salamanders to goatfolk. The merchant’s guild, the water barons, and the villagers of every settlement in the land - these will all accept a “water ritual” as a means of bonding and improving reputation, and will all maintain some opinion of you as you explore, graverob, and offend.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

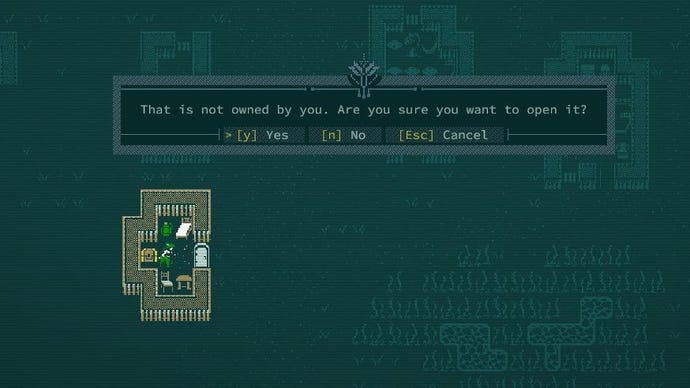

And offend you will, if only because you may not know what you’re otherwise supposed to be doing. Those who crave firm direction in questing may feel adrift at the introduction, a single line that reads: “You embark for the Caves of Qud.” There’s a main quest which is really a chain of quests that don’t always appear to be related to each other (the final parts are the main attraction ofthis month’s 1.0 release). But they’re still worth doing as a beginner, because they offer a lot of XP to be pumped into unlocking new mutations. And they’ll get you on the loot train, choo-choo-ing all the way to a full suit of ogre fur armour, or whatever equipment is dropped in your game world. One of the more confusing selling points of Qud is its procedural generation. Or to be more accurate, itspartialprocedural generation.

The game is not 100% random every run. The big world map will always look the same (the salt dunes are always to the west, the spire is always to the north). But at the down-to-tile level of a little guy walking around the countryside, the caves themselves will be different, the loot randomised, the enemy types altered. Villages and other important locations remain the same, but the “history” of the world is random. You can see why things might get confusing. This combo of random and unchanged elements can feel inscrutable, even as it adds mystery and variety.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

And what variety. There is a depth and colour I won’t be able to communicate in a single review. You can get lost while you cross the world map, and will be forced to explore new areas to get your bearings. A bloated leech may just as easily be employed as a hired guard (“I’m watching you, traveler”) as attack you wordlessly in a dank cave. Books you find may be called things like “Aphorisms About Birds” or “On the Origins and Nature of the Dark Calculus” or “OPERATING MANUAL FOR LARGE CREATURE” (these are not randomly titled but they are randomly placed and grant XP when donated to a special librarian).

There is a peculiar joy to working out the rules of this world. The game is a mechanism in and of itself. You can fall downa wiki hole about Qudin the same way you can fall down a wiki hole in life. And you will go there in search of answers, without a doubt. But seeing things firsthand before seeking a guide is, for me, a more enjoyable way to discover the world and its rules. I have gotten badly hammered on cave wine, the symbolic spritework of the world getting jumbled beyond recognition in a perfect replication of the sickening dizziness of reading while drunk. I have teleported as an act of desperate escape, only to misfire and appear in a locked room with seemingly no way out (I took advantage of the peace, made a campfire and ate some chickpeas). But my favourite Qud-tale is about a goatman called Indix. Stick with me here - I know this review is long - this is my final effort to convince you that you should play this game.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games

I find myself in a mushroom village, where a stocky goatman is standing watch. I approach him and say hello. He is known as Indix, the “pariah”. I ask why he’s called that - “pariah”. But he warns me not to ask again. I take the hint and change the subject. I want to be on good terms with these villagers. I am a musketeer. I need any bullets they have to sell.

My curiosity is too much. I ask the capricious capricorn why he is a “pariah”.What did he do?Again he warns me not to go there, it isn’t a subject he wants to talk about. No, really, I say, I gotta know. He reacts to my prying questions, let us say, passionately.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun / Kitfox Games